Sir Simon Fraser of Neidpath, can be thought of as the founding father of the Lovat Frasers. Born in 1257 in Neidpath Castle near Peebles, he met a gruesome death in London in 1306. He had been captured fighting in the Scottish Wars of Independence.

One chronicler calls Simon ‘a man totally gifted for war’. Another hailed him as ‘manly, stout, bold and wight’ – meaning brave and nimble.

Sir Walter Scott thought Sir Simon was ‘the flower of chivalry’. In that turbulent era, Sir Simon and most of the Scottish elite, tried at times to work with the English king, Edward I, who continually threatened the Scottish borders. Edward claimed the right to interfere in the government of Scotland. Sir Simon alternated this policy of tolerating Edward’s intrusion, with periods of taking up arms to keep Edward out of Scotland.

Simon the Patriot’s most astonishing achievement must be the Battle of Roslyn. It took place in 1301. A bloody and significant battle in the Scottish Wars of Independence, today it is mostly forgotten. With only 8,000 men, Simon led the Scots army to victory over an English invasion force of over 30,000, using his superior knowledge of the terrain and the element of surprise.

Simon the Patriot and the battle of Rossyln

An uneasy peace lay on the land after English and Scottish lairds agreed to suspend hostilities in the Wars of Independence and signed a truce at Dumfries in October, 1300. It collapsed in February, 1303.

The background to its collapse was a marriage contract. Scottish nobles made plans to marry John Balliol’s daughter to a French princess. John Balliol was Edward I’s puppet king of Scotland. Edward opposed the marriage. He was determined not to allow the Scots to take a line in Scottish foreign policy that was independent of England’s. Marital contracts were also foreign diplomatic events. And Edward refused to accept this Franco-Scottish alliance on the English border.

Edward I made John de Seagrave governor general of the land Edward called the ‘Province’ of Scotland. Edward now allowed Seagrave to invade to stop the marriage and bring the Scots back into submissive line.

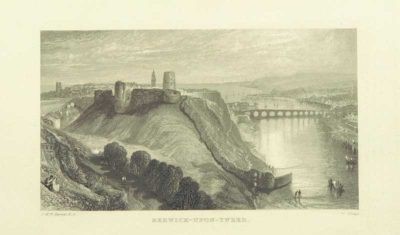

Seagrave gathered an army of between 20-30,000 men and crossed the border from Berwick. Seagrave’s intelligence told him there was a resurgence in allegiance to Scottish nationalist patriots, who loathed Edward’s order that the Scots acknowledge him as their overlord. Edward instructed his commander to bring the Scottish patriots back to heel. Seagrave must root out anyone seeming to threaten the ‘peace’ of the truce, to give no quarter if any resisted, and lay their country waste.

To the Scots, this looked like Edward breaking the very peace he claimed he was securing by an invasion.

Seagrave’s army moved towards Edinburgh. He split it into three divisions, each numbering 7-9,000 men. The army deployed to raid three different locations simultaneously, to confuse and overwhelm Scots’ plans to resist him.

How to react? The Scottish patriot leaders met. William Wallace, one of their key figureheads, refused command. Wallace believed he had lost the confidence of his officers for the time being.

Berwick upon Tweed

Wallace appointed Sir Simon Fraser to be supreme commander. Sir Simon mustered an army of around 8,000 as fast as he could –it was about one third the size of the English invading force. Accompanied by Wallace and John Comyn, Simon Fraser’s army marched out to meet the enemy, unaware they had split in three separate forces.

By now, one English division was marching on Borthwick Castle (12 miles south-east of Edinburgh), one marching on Dalhousie Castle (8 miles south of Edinburgh), and one was crossing Tweeddale – Simon Fraser’s territory – to close on Rosslyn (10 miles south of Edinburgh).

The whole Scots’ army marched to Rosslyn. Sir Simon sent John Comyn and 3,000 men to hide themselves in the woods on the west bank of the river Esk, which runs through Rosslyn Glen. He took the remaining 5,000 round the back of the enemy camp, and approached in a crescent shape. An hour before dawn, Sir Simon and his men began to creep towards Seagrave. At the last minute, the Scots charged into the sleeping encampment, hacking and slashing and creating chaos. Seagrave’s men died, or fled across the river into the forest – and into the hidden Comyn’s waiting arms. Seagrave, wounded, surrendered to Wallace. Simon Fraser’s men began to gather plunder.

News spread to the other English divisions. Discovering there were two more armies, the Scots regrouped and lined up on top of Langhill to the northwest of Rosslyn. The second army under Ralph the Cofferer (Edward I’s bag man) abandoned their siege of Dalhousie Castle, and marched to Rosslyn. Spying the enemy, they charged up the Langhill. Arrows rained down on them and broke their charge. The English turned and hared off to the north.

The river Esk runs through Rosslyn Glen

Unknown to them, they set themselves on a path towards a sheer drop off a ravine into the river. When they saw their error, they were horror-struck, but it was too late. Those in the vanguard found themselves pushed over the edge of the ravine by the momentum of those behind them, trying to flee Sir Simon. Those in the rear were driven off the crag by Scots pikemen and archers.

A butchered heap of hundreds of horses and men and arms lay tangled in the burn, dead or dying. The cacophony of the dying must have chilled the blood.

No time to rest. Scouts rode in to announce the third invading force was almost on them. Those among the English troops who had not died in the carnage at the ravine were now slaughtered. Sir Simon feared they would take up their arms again one they knew help had arrived.

The Scots were exposing themselves to acute danger. They had route marched all night to get here at all. They had now fought two battles. Adrenalized from the victories as they were, they had very little energy left to draw on. Having decided they could not risk taking prisoners in the clash at the ravine, the exhausted soldiers knew they could expect no mercy themselves if they lost to this third force.

But English intelligence failed them. The third division had no idea what befell their second division. So they marched along the low road into Rosslyn glen. The Scots took up positions on Mountmarle, west of the English troops. To the east lay more cliffs with a 100 foot drop into the river bed. The Scots used the same tactic – a storm of arrows caused the enemy to wheel eastwards away from them, and thousands more fell to their deaths, many with swords unsheathed, and arrows undrawn.

Surrounded by the catastrophic losses to the English, Simon could afford leniency at last. He cried that ‘Quarter’ be given to the survivors and let them run for their lives. Some thought only 10% of the English army returned across the border to tell the tale.

It is an old army truism that time spent on intelligence is never wasted. This was Simon Fraser’s country. He had all the information he needed about the terrain, and used it to terrible effect. In his hands that dramatic river valley became a mighty weapon. And he won one of the most important victories in the First Scottish War of Independence. (with thanks to John Ritchie’s excellent account, reproduced on The Clan Sinclair (http://sinclair.quarterman.org)

When you visit Rosslyn Chapel today, looking for signs of the Knights Templar from the 1460s, that Dan Brown used in The Da Vinci Code, it is worth taking a quiet walk up the valley by the peaceful River Esk, to listen for even older ghosts sighing in the shade of the glen.

Scotland during the wars of Independence

In the early 1300s, magnate factions battle for dominion over Scotland. On one side, Edward I of England worked to force Scotland to submit to English domination. Edward preferred bedroom politics if possible. He wanted key Scots to build up a landed interest on both sides of the border. This included the Frasers. The leading families formed bonds via strategic marriages with English heirs and heiresses. Gradually, old native Scottish families began to unite with English and Norman elites, and share their priorities and values.

But some preferred to be Kings in Scotland than Lords in England. Many Scottish nobles switched back and forth, as they resisted, or submitted and swore fealty to Edward. This was the path Simon Fraser followed for several years.

In the end, William Wallace, Sir Simon Fraser of Neidpath, Robert the Bruce, and their supporters committed themselves and their people to independence, and freedom from Edward’s overlordship. They fought out their struggle in The Scottish Wars of Independence.

Robert the Bruce

Sir Simons Luck runs out

Two years after the incredible victory at Roslyn, Simon’s brother-in-arms, William Wallace was betrayed and executed. Simon then gave his loyalty to Robert the Bruce, who was crowned King of Scotland in March, 1306. Simon the Patriot rode at the Bruce’s side at the Battle of Methven in June 1306, to rid Scotland of Edward’s invasion force.

This time the English army had surprise on their side. They mounted a lightning attack. Three times the Bruce was unhorsed, and each time Simon helped him back into the saddle, fighting off the enemy. It was said that the Bruce granted the Frasers the right to display three crowns on their arms after this, to signify the number of times they had saved the Crown of Scotland.

Yet, in truth the Scots barely escaped, and fled into the Highlands. On the run, the Bruce nearly gave up the fight. Simon Fraser could permit himself no such luxury as to think of surrender. He knew what it would mean for him. But, encountering English soldiers at Kirkencrieff, he was taken prisoner.

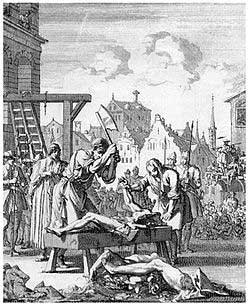

They carried him to London in irons. There, they tried him and condemned him to the refined cruelty of a traitor’s death. On 8th September, 1306, he was dragged out of prison and marched in mockery from the Tower to London Bridge. There Simon Fraser was hanged, and cut down while still alive. They disembowelled him, threw his guts into a brazier, and then beheaded him and cut off his limbs.

A traitors death

The executioners stuck Simon Fraser’s head on a spike beside Wallace’s, on London Bridge, and hoisted the trunk of his body, in chains, to swing close by. Londoners claimed they saw demons rampaging along the parapets, and tormenting Fraser’s remains with hooks.

Hang, draw and quartered

450 years later, another famous Fraser leader, Lord Lovat of the ’45, stood on his own scaffold in London in 1747, waiting to be executed for treason for his part in Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Jacobite rebellion. Lovat declaimed the Latin poet, Horace. ‘For those things which were done, either by our fathers or ancestors, and in which we had no share, I can scarcely claim for my own.’ It was these old heroes of Scottish independence Lovat saw in his mind’s eye, as he waited for the axe to fall. He saluted them, his imagination soaring above the crowds baying for his head.